Dewdrops sparkled across a broad sandy lowland field waiting to embrace its spring tobacco seedlings. This annual event dates to the 1600s, the early colonial days of Southern Maryland. For many colonial tobacco planters, farmers, and workers, tobacco became a cash crop and a family curse.

Southern Maryland, blessed with tidal and fresh waterways, provided settlers with ideal hunting, fishing, and farming areas. Large land tracts, granted by Lord Baltimore, land he is said to have bought rather than stolen from native peoples, enticed English adventurers to seek religious freedom and economic opportunity. Many early Maryland settlers were of the upper class, who brought tradesmen and indentured servants with them to perform the work of establishing settlements. Indentured farmers tended crops, but the slave trade soon followed with the introduction of tobacco cultivation from the Virginia colony. Indentured servants then enslaved people felled forests. Lumber was shipped to the Caribbean or England, with needed goods returned to the colonial landholders. Subsistence farming provided food for the settlers’ families, their servants, and slaves, but it was tobacco that produced wealth for the planter-class landholders. When gold and silver currency were scarce, tobacco was substituted as currency for trade during the colonial period.

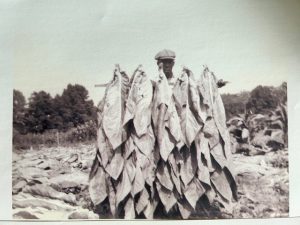

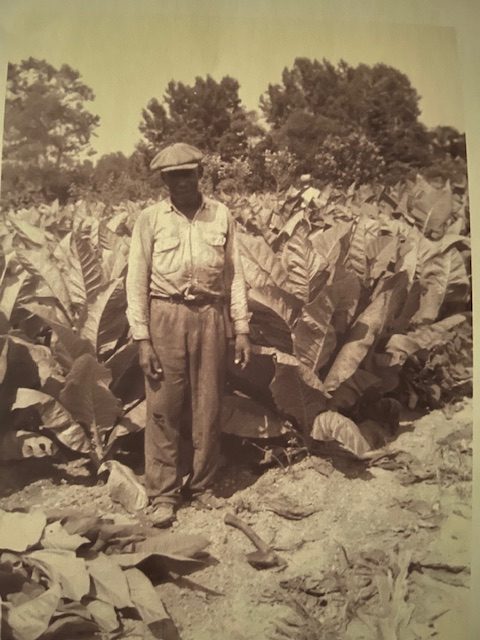

Tobacco was a labor-intensive crop. Tiny tobacco seed, planted in early spring under a frost cover of cotton muslin, sprouted after rain or hand watering. When the seedlings reached six to eight inches tall, they were uprooted for transplanting in prepared field tobacco rows. The seeding, watering, uprooting, transplanting, weeding, tending, topping, cutting,

spearing, hanging, curing, stripping, packaging, and selling involved about nine months of dirty, difficult, skilled manual labor without the benefit of machinery until the tractor and tobacco planter came into use in the early 1900s. The tobacco production process, from seedling to sale, requires the utmost delicate care to prevent tobacco leaf damage, ensuring quality control for its end user—to sniff, chew, or smoke.

Maryland’s tobacco planters were concentrated in the southern portion of the state, one of the largest tobacco-growing regions in the country. During the mid-17th century, Maryland and Virginia tobacco planters exported most of the tobacco sent from Colonial America to Europe to meet its ever-increasing demand. Maryland’s light air-cured tobacco was prized for its thin leaf and free-burning quality.

Several social events celebrated the tobacco harvest, including a pageant, the crowning of Queen Nicotina, introductions of her court and escorts, and a formal dance. Years passed and traditions changed. On September 12 – 15, 2024, Maryland’s Charles County Fair Board will celebrate the 100th year of nominating, selecting, and crowning Queen Nicotina, presenting her with a college tuition scholarship.

In Southern Maryland, slavery replaced indentured servants as a cheaper source of labor. Many Maryland slaves of African descent, imported from Caribbean sugar plantations or purchased from tobacco planters in Virginia, were skilled workers and spoke English. As Maryland boundaries expanded, slavery followed but to a lesser degree. Tobacco did not grow as well outside of Maryland’s tidewater regions, limiting the need for slave labor.

The ratio of European settlers to slaves (40:60) during the peak of the slave trade in Southern Maryland remained essentially unchanged until the 1920 U.S. Census when black populations began to migrate. Today that trend is reversing due to white flight. A recent U.S. census showed an almost identical ratio (40:60) of white to black population in Southern Maryland, with the black population remaining in the majority as it had since the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. “The Land of Pleasant Living” seemed to keep most black families in place, benefitting from employment opportunities in expanding nearby towns and Washington, D.C., Annapolis, or Baltimore, all within reach by horse, boat, train, bus, or car as time advanced. When nearby cities and government employment grew, Southern Maryland became a bedroom community for black and white workers. Former large landholding tobacco growers, who depended on tobacco for their livelihood for generations, began to raise a new crop – subdivisions.

The 1964 Surgeon General’s report on the hazards of smoking tobacco decreased demand, but tobacco continued to be grown in Southern Maryland, and sold to tobacco company buyers at local warehouse auctions until the late 1970s. Tobacco farming shifted, performed by Amish and Mennonite families, relocated from Pennsylvania to Southern Maryland, who wished to keep their children on the land with year-round work. Cultivation of tobacco filled that need, and tobacco corporations began purchasing tobacco on contract from individual tobacco farmers. Maryland’s 1998 Tobacco Buyout Agreement used money from its share of the national Master Settlement Agreement with tobacco companies to pay farmers not to grow tobacco, causing tobacco production to decline. Today, few tobacco farms remain in Southern Maryland. Tobacco’s high production costs of the labor-intensive crop have left a few struggling farmers and sentimental “tobacco garden” hobbyists who continue the tobacco growing tradition.

Slaveholding planters and other tobacco growers in Maryland and elsewhere reaped the profit, then the curse from tobacco when they or family members died of cancer from sniffing, chewing, or smoking the weed or from breathing secondhand smoke. Descendants of slaveholders carry the stigma of their ancestors’ owning people, but some descendants of formerly enslaved families carry the stigma of possessing British or European genes in their DNA.

We cannot change the past; we can learn from it. Regardless of our cultural and ethnic backgrounds, we must respect each other as human beings, and we must never repeat misdeeds like those along Tobacco Row.

Chuck Bins • Aug 5, 2024 at 10:42 am

Thank you for your historical perspective on tobacco farming and for highlighting the impact on both those who grew it and those who tended the fields. Of course, tobacco still enslaves many consumers, often from a young age. As Sir Walter Raleigh once pointed out: “Tobacco only feeds the habit it creates.”